The view into Cindy Sherman’s studio via Zoom paints a portrait of one of the greatest artists of our time, in lockdown. She’s spent much of the past year ensconced at her home in a sleepy corner of East Hampton, New York state, with her boyfriend and his dog. Behind her, suspension training straps hang from the ceiling and a yoga mat is on the floor. In the corner of the frame, a potter’s wheel is just about visible — lately, Sherman has been satisfying a long-term itch to work with her hands and experiment with the medium of clay, something tangible in a world where the virtual feels indistinguishable from reality.

Sherman’s foray into ceramics is congruent with the creative direction she was taking before the pandemic. Since 2019, alongside major retrospectives at institutions such as London’s National Portrait Gallery and Paris’s Fondation Louis Vuitton, she’s been turning the images she posted on her Instagram into tapestries. These are the first non-photographic works she’s created in a career spanning more than 40 years, and nine of them are now on display at Sprüth Magers gallery in Los Angeles.

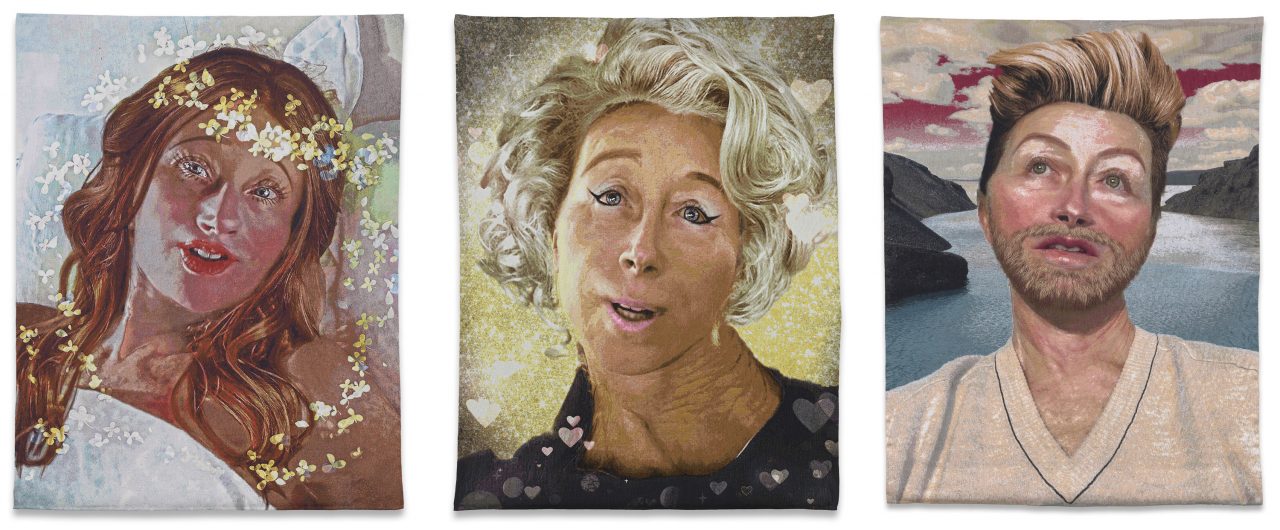

Cindy Sherman (Left) Untitled, 2019. Cotton, wool, yarn, acrylic, mercurisé, and Lurex woven together, (centre) U ntitled, 2019, Polyester, cotton, wool and acrylic woven together, (right) Untitled, 2020, Polyester, cotton, wool, viscose, acrylic and cotton mercurisé woven together.

Photo: courtesy Sprüth Magers and Metro Pictures, New York

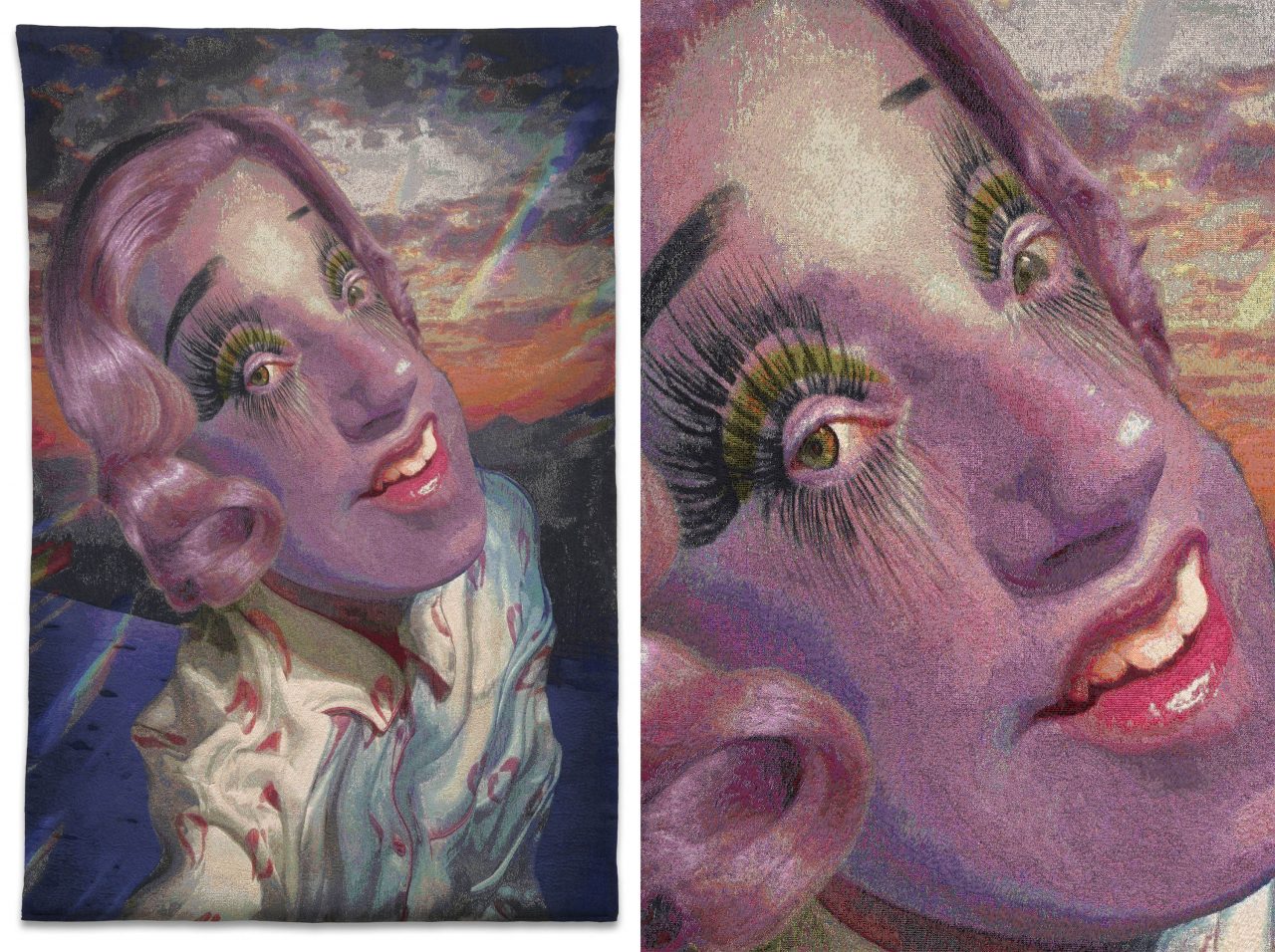

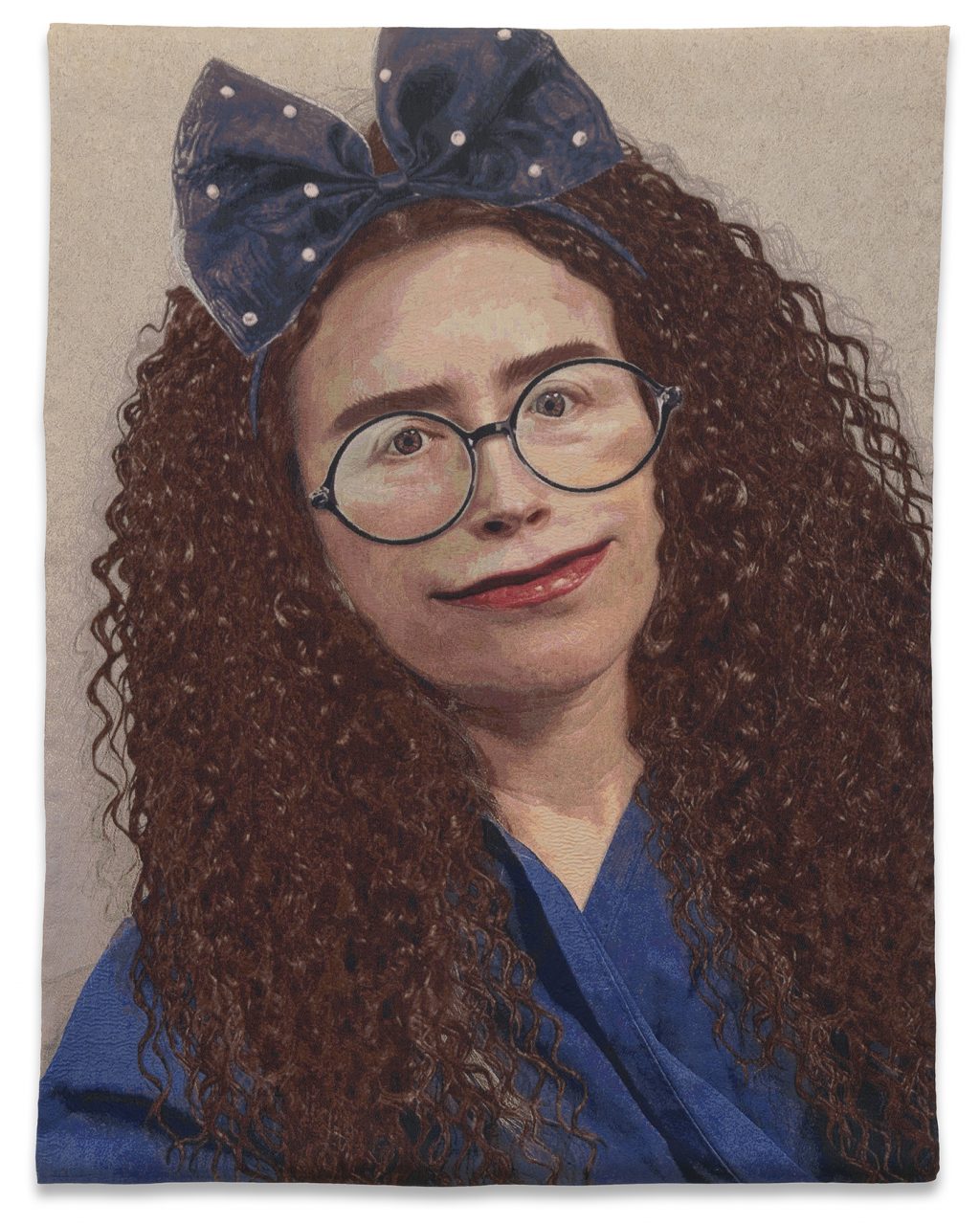

The textiles, which are made from fibres including cotton, wool, acrylic and polyester, were produced in Belgium in tribute to the country’s centuries-old weaving traditions. Sherman assumes a different character in each tapestry, transforming herself through clothes, accessories, eye and hair colour; through inhabiting different genders and manipulating her facial features.

These chameleon-like traits are, Sherman says, an act of erasure of self rather than a revealing of hidden fantasies, which viewers often project on to her work. In doing so, what perhaps also gets lost is the joy the 67-year-old gets out of creating new characters, as she explains: “I like seeing how far I can get from what’s familiar; it’s just fun, always has been — ever since I was a kid.”

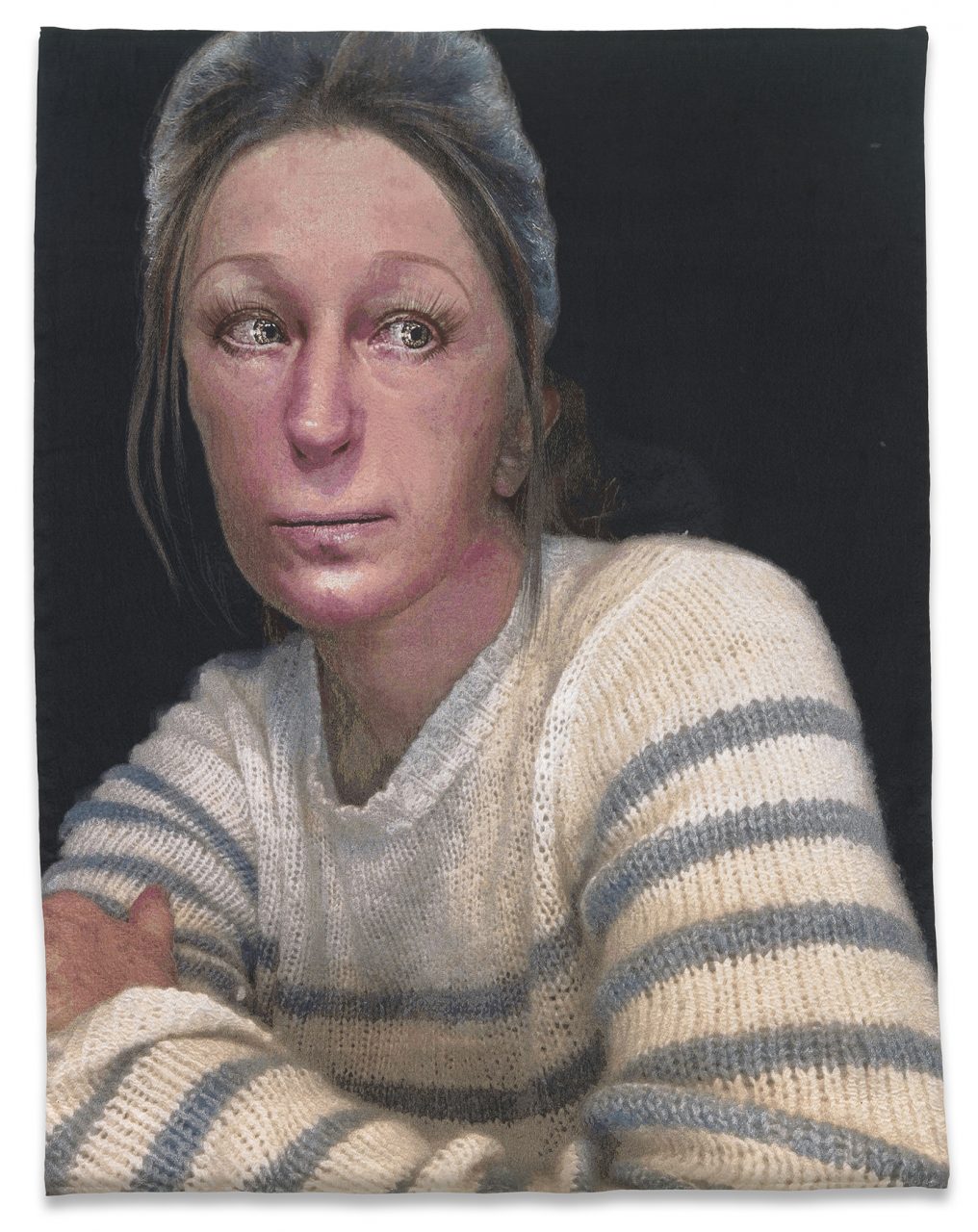

Cindy Sherman, Untitled, 2019. Cotton, wool, acrylic, cotton mercurisé, and polyester cotton woven together.

Photo: courtesy Sprüth Magers and Metro Pictures, New York

When did you first get the idea to make tapestries?

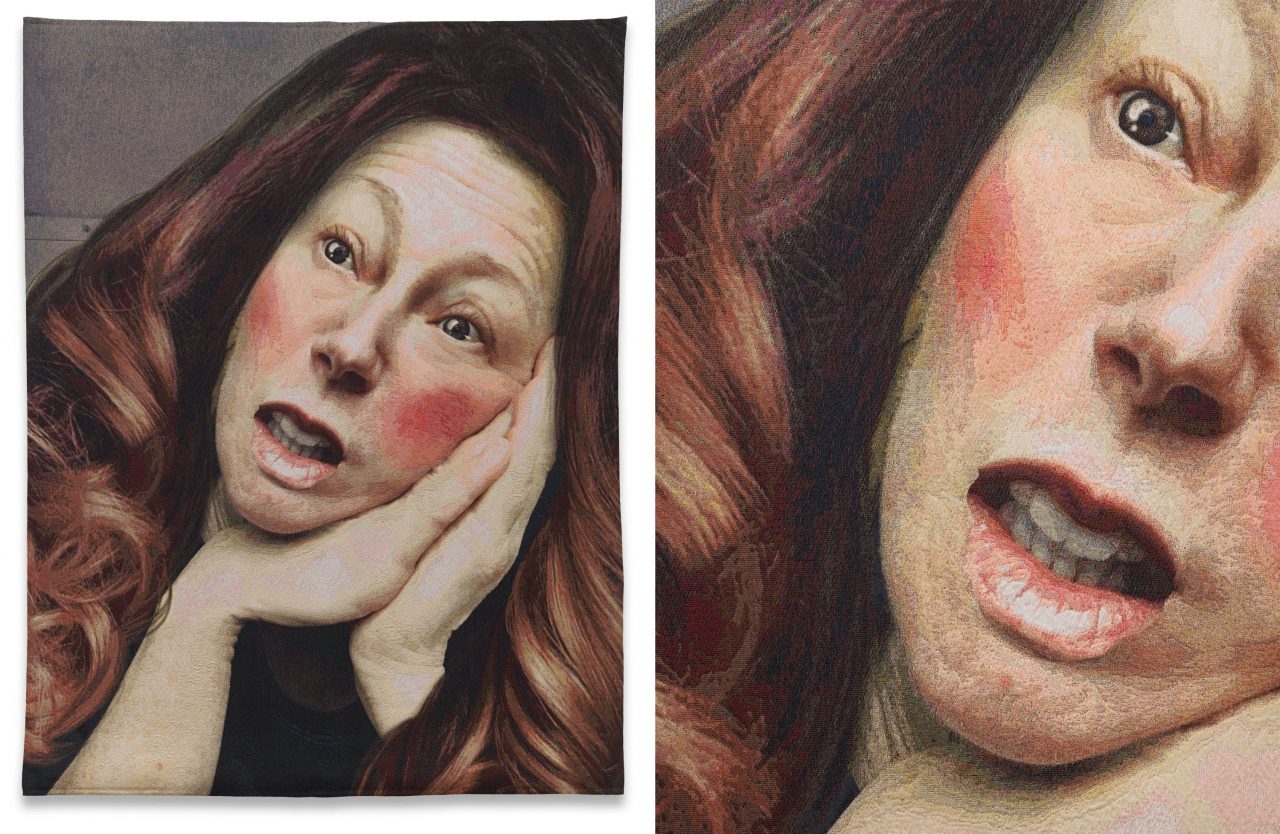

“I originally looked into the idea about 12 years ago. I made some samples with a company in California — the quality was fine, but I didn’t like the way it looked. The image was a full figure so you lost all the detail; you couldn’t get a sense of the person’s face at all. It was just a bunch of stitches. I remember thinking then it would work really well as close-ups.”

How did the process evolve?

“I couldn’t put the thought aside. I had all these Instagram images that I liked, but I didn’t know what to do with them. They didn’t work as [large scale] photographs because they were all taken on a phone or iPad. The transition to tapestry worked really well because it’s like an old-fashioned form of pixelating — everything meshed together nicely.”

What have you come to like about textiles and clothing as a means of self-expression?

“Textiles I like for their tactility. Tapestries specifically have a three-dimensional quality, just looking at the range of skin tones and the way it builds up over the course [of it being made]. It looks very topographical; not like skin after a while; abstract almost. Clothing is a whole other story. There are so many ways fashion can be expressive and exciting.”

Cindy Sherman, Untitled, 2019. Cotton, wool, acrylic, cotton mercurisé, and polyester cotton, woven together.

Photo: courtesy Sprüth Magers and Metro Pictures, New York

You’ve spent most of the past year in the country. Do you miss New York or has it made you rethink how you want to live your life?

“In the country, there are actually more distractions, happy distractions like in the summer when the weather’s warmer, you can go cycling or do gardening. Of course, I’ve really got into baking a lot and so I’ve [developed] this impulsive feeling like, ‘Oh, I must make more sourdough starter.’”

“But I don’t know if I would want to be out here full-time. It would be really hard to make the choice to give up what the city has to offer. They both balance out each other in a nice way.”

Your practice is pretty self-sufficient in that you use yourself as a canvas, but do you ever get lonely?

“I’m a loner so it doesn’t really bother me. Right now, I miss my friends and family, but we keep in touch through email, texts and sometimes Zoom or FaceTime. But I don’t miss the dinners and gallery openings as much as some people.”

Cindy Sherman, Untitled, 2020. Polyester, wool, acrylic, silk and cotton mercurisé woven together.

Photo: courtesy Sprüth Magers and Metro Pictures, New York

I read that you have created in the region of 650 characters. Do you have any particular favourites that you find yourself returning to?

“I haven’t kept count, but that sounds about right. I like the recent characters, but usually if I feel like I’m repeating myself, it’s time to move on. It’s definitely more challenging every year to think about how I’m going to take it to the next level.”

A Cindy Book — an album of family photographs that you began compiling as a child — was such a memorable part of your London retrospective and showed your early fascination with changing your appearance. What are your memories of creating it and what would you say to that girl now?

“I was around six years old when I started it. My family kept the family snapshots in old shoe boxes and I loved going through all the photos, looking for bits of myself or my past. I’m the youngest of five and there was a big age difference between me and the rest of [my siblings] so my family had a whole life before I was born. Part of the idea of creating these pages was to locate myself within the family or social unit. I don’t know what I would say to that kid, maybe: ‘You need some psychotherapy [laughs].’”

Cindy Sherman, Untitled, 2019. Polyester, cotton, wool, and acrylic woven together.

Photo: courtesy Sprüth Magers and Metro Pictures, New York

You made your Instagram public in 2017 — has social media impacted the way you work?

“Some of the apps, such as Facetune and Perfect365 which I use to transform the images, have impacted my work more than Instagram itself. They made me think about filters in a different way; things that I otherwise wouldn’t have done in Photoshop. It’s been fun but I think I’ve run the gamut of where it can take me.

“I use social media very sporadically. Sometimes I have no desire to go on it, other times it’s nice to feel connected to people again and see what they’re up to. I hate the feeling that I’m dependent on something. There was a time when I’d get into bed at night and go on Instagram. Lately, I’ve been picking up a book instead.”

Are there any books in particular you’ve enjoyed reading recently?

“I read Elena Ferrante’s The Lying Life Of Adults (Europa, 2021) and that was really great.”

Cindy Sherman, Untitled, 2020. Polyester, cotton, wool, acrylic and cotton, mercurisé woven together.

Photo: courtesy Sprüth Magers and Metro Pictures, New York

The term ‘female gaze’ is broadly applied to the work of women artists. What are your thoughts on the term?

“Growing up, I was definitely very aware of what was expected of me in terms of becoming a woman and femininity. Particularly at college, I questioned and started resenting these expectations. I wasn’t aware of the term [female gaze] until I read a review of my work. So it was never something that I had articulated. The early film noir work [1977 to 1980] and all my work since is about questioning what’s expected of me in society.”

Cindy Sherman: Tapestries is on until 1 May 2021 at Sprüth Magers in Los Angeles, US

Editor

Liam FreemanCredit

Lead image: courtesy Sprüth Magers and Metro Pictures, New York