“I’m curious all the time,” says King. In a recent conversation with American artist Clinton King, revealed his insatiable desire for exploration and discovery. Known for his diverse artistic practices spanning painting, sculpture, and video, he is a curious soul armed with enthusiasm for the boundless possibilities that lie within the realm of creating on flat surfaces.

He quotes Friedrich Nietzche’s, “We have art in order not to die of the truth,” highlighting his belief that art serves as an extension of our realities. Examining King’s extensive body of work, transformation emerges as his preferred medium. His paintings encompass a diverse range of imagery, simultaneously open and uniquely singular in their expression. King’s artistic approach embraces a minimalist philosophy, yet yields elaborate and maximalist effects.

Despite not being King’s first visit to Hong Kong, it marked a significant milestone as he showcased his first solo exhibition in the city at WOAW Gallery. Titled “Moonshine,” this exhibition presented a captivating collection of King’s latest oil paintings, where each artwork reflected his unwavering commitment to openly explore and discover his artistic practice. With every brushstroke, he skillfully constructs intricate patterns that pulsate with vibrant energy and emotion.

As we delve into King’s psyche, we peer beyond the canvases to uncover the essence of his inspiration and creative process.

Moonshine Exhibition, WOAW Gallery

Photo: Courtesy of WOAW Gallery.

How does it feel to be back in Hong Kong for your solo exhibition at WOAW Gallery?

I’ve noticed that the city is a lot busier than when I was here just five months ago. And there are a lot more tourists here right now. But I didn’t know what to expect, to be honest. I have many friends who are here now, but I haven’t even seen them because everyone’s so busy. Plus, there are so many openings! I was at first worried that I was going to be sidelined or something. But in fact, my gallery opening was one of the best openings I’ve ever had. And I enjoyed it so much. I’m very impressed with it and with the amount of people who came in, and the gallery really pulled through. I’m very familiar with art fairs. I’ve been to all over the world on these, but I just feel at home in Hong Kong. I feel at ease here. I feel great being here and it’s not as intimidating as I thought it was going to be.

How do you feel before a new opening and what was the opening of your latest exhibition “Moonshine” like?

I usually get pretty stressed out, to be honest. There’s some anxiety, but there’s also some excitement there, of course. There’s always a bit of a nervous feeling about how the exhibition will be received, or if anyone will show up. That’s always the worst thing that could possibly happen. But I’m always impressed with the genuine responses that people have and I’m also very interested in hearing them from people who are not familiar with artwork, who sometimes kind of wander into the space. Just like the other day, they asked me some of the most interesting questions that the average person doesn’t ask. And I find those questions to be not only curious but also enlightening. The questions that are asked and the references that are made here are at times different than in other places. For instance, somebody had brought up the idea of the mark in my works, such as calligraphy or writing. I’d thought of that in the past, but I’d kind of forgotten about it. In the West, you wouldn’t expect these references because we don’t have that history of what a bold single stroke could mean or the history of linear language and writing, which has a much different meaning and history in Asia and is more based in abstract expressionism than in the West.

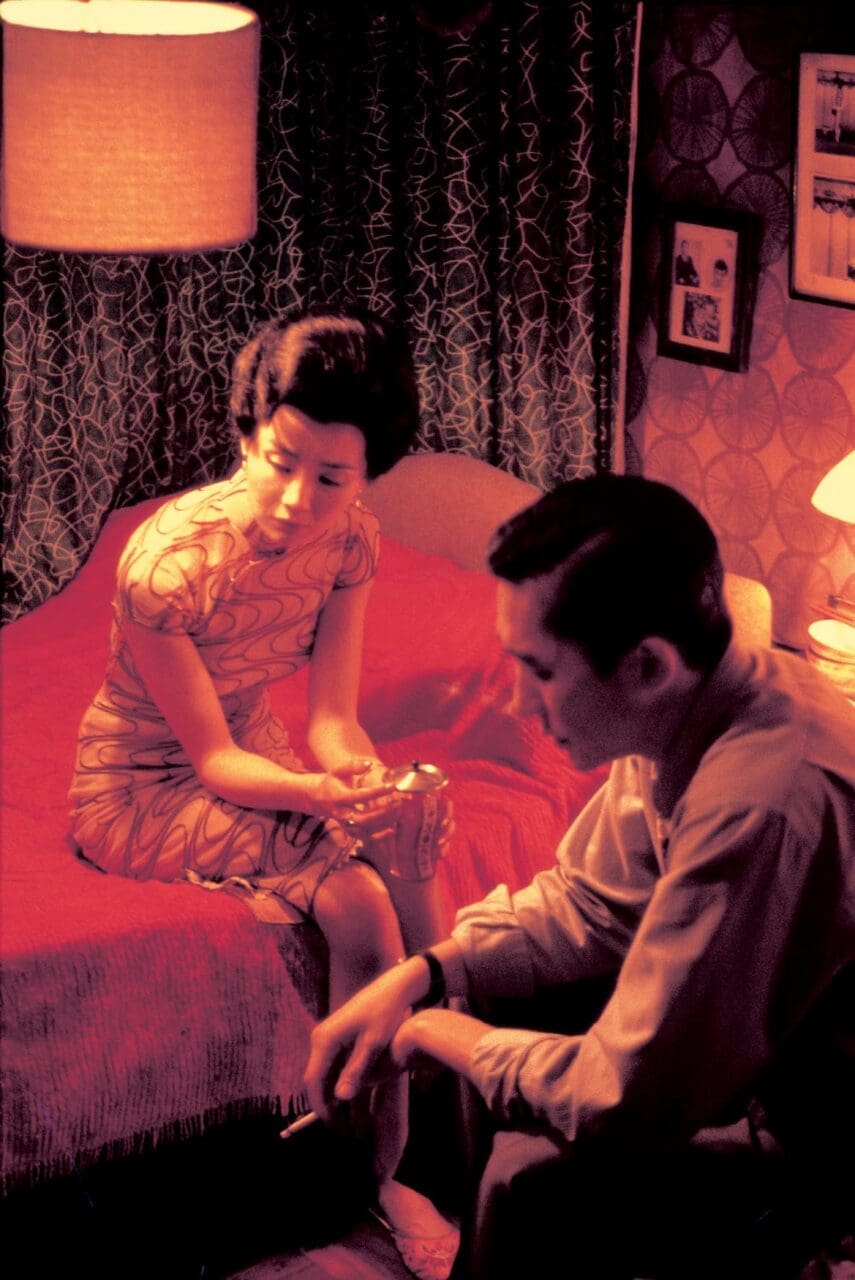

Moonshine Exhibition, WOAW Gallery

Photo: Courtesy of WOAW Gallery.

You’ve held exhibitions across Asia. What do you think about the growing interest in art in the region?

Arts in Asia is really coming up. And I think a lot of that interest in art, mostly among the general public, has a lot to do with the graphic street art culture that was a first introduction to a lot of people. I think that flat, graphic, bold colours and bold movement seem to be a trend that I’m seeing. So I feel like the work is read differently here and people are seeing it differently too. That cultural background results in seeing and interpreting things differently and I find that to be the most interesting.

How would you describe your practice?

If I were to go into the idea of openness, the work itself is very open, and my practice is also very open. And that’s key to me; that the work isn’t trying to be anything other than what it is. It leaves anyone in any culture and country, from any age to come and experience the work. There is no theory or particular idea that I’m trying to get across. I am trying to actually be the exact opposite of what this movement is and to be as open as possible.

Where does that come from and what does it mean to you?

Whenever I’m making a painting, sculpture, or video, I see it as a relationship. I am not here to illustrate a concept outside of an open relationship. I ask the work to meet me halfway. I make a move and I ask, “What does it need, what does it want?” If I try to impose my will on it too much, the marks feel constricted. But instead, I ask, “What does the painting want?” The painting is much smarter than I am. It knows what it wants to become. I didn’t know to what extent I was working like that until I developed my practice enough to understand that it’s not will pushing me from behind to create a particular type of art or painting. I put the painting in front of me and it pulls me forward. The painting has to be beyond me.

In the sun's shadow, Clinton King

Photo: Courtesy of WOAW Gallery.

Can you tell us more about your creative process, specifically the practices you’ve developed in your latest collection “Moonshine”?

The process that I’ve developed allows a lot of openness, and it’s mainly because I’ve reduced the painting down to a very simple stroke. I am trying to give as much information as I can with the simplest mark. The marks have all the qualities of an oil painting; blending, value shifts, and chromatic shifts. I try to get as much information and the highest resolution possible with the simplest of strokes, and then I play with some loose set of rules, and I don’t know where it’s going to end or how it’s going to end! If the work surprises me, it’s most likely going to carry that energy into the viewer’s experience, I hope.

The paintings carry very distinctive titles. How do you decide on the name for each piece?

It’s usually a very intuitive thing at the very last second. I have a record on my phone with a very long list of titles, almost like a haiku and they are things I’d pick up when I’ll be reading something or I’ll overhear a conversation. I go through the list and I’ll find a title that fits the painting, or it just usually pops up! In terms of “Bramble”, it was a stand-in word but then I just ended up embracing it.

You often explore opposites in your work, such as order and disorder, tangible and intangible. What is it about these dichotomies that attract your attention?

I think it’s like life! There’s night and day; we sleep, we awake, we live, we die. We’re happy, we’re sad. But I’m interested in the spectrum in between that as well. We all have a relationship with the opposites of life and where we fit in at any time. Sometimes I look at the paintings and they feel very menacing. Sometimes they feel heavenly. Sometimes they’re even sublime.

Transformation also appears to be a continuous theme in your works. What draws you to it?

It’s all about transformation and transition. I studied Tai Chi before and this practice is all about transition. Also when you listen to House or electronic music, you will notice that it’s all about transition. I used to also do up-close magic and I studied magic as a sort of philosophy, so I’m very fond of magicians. For me, magic is about establishing patterns and breaking them. Comedians also establish patterns and break them. These transitions are everything to me. An artist friend of mine, Peter Shear, said that sometimes he slams something down on his canvas just to fix a mistake. The artist makes a mistake for himself to correct.

Feedback cascade, Clinton King

Photo: Courtesy of WOAW Gallery.

What has had the most influence on your work?

Everything. Everything I’ve ever liked and everything I’ve ever hated is in the painting. I think it’s impossible to completely flush out any influence. You’ll respond to the things you hate as strongly as you respond to the things you love.

Have you ever surprised yourself with where some of your inspiration comes from?

One time I had a dream of a painting first. I told my wife that I made a painting with all these single marks and she told me that I should just make it! That kind of stuck in my head and so I made a small one just to see if I could do it and that it was possible. I proceeded to make a slightly larger one and then the process got faster. I realised that this was a dream come true.

You’ve explored various creative mediums like painting, sculpture, and video. Do you feel each process is unique?

I’ve actually felt the shift in my brain when working with different creative mediums. I feel very different working in sculpture than I do in painting. It’s a much different response because sculpture has its own set of rules and every material has its own limitations and its own breaking point. Whereas painting itself has its own way in which it’s read and it has a much constrictive area on canvas. Sculpting is three-dimensional, and it has a face and a back and I feel like that is very spatial thinking and it’s very different.

Are you considering taking any of these mediums further?

Yes. I was a painter who turned sculptor. A sculptor who turned to video. And I’m doing bonsai trees right now. It has nothing to do with art. I’ve also dabbled in martial arts since I was a teenager and now I’m getting involved in many other things. But it all eventually comes down to this: the broader your spectrum of tools and understanding becomes, the more you can give your creative process to work with. All my art will thank me for the other things I’ve done. Even though it’s not apparent to the viewer, it gives me more angles to approach.

What will you be taking away from this trip to Hong Kong?

I feel confident again. I was worried that the work was stagnating and so I needed the work to be seen. It was refreshing to hear the people’s response to it and it has revitalised my desire to make work again when I’m back in the States.

Editor

Hala KassemCredit

Lead image: Courtesy of WOAW Gallery