“Stella came off the train from Scotland smelling of goats,” Isabella Blow chortled down the phone to me. It was the summer of 1993 and Stella Tennant had been scouted for the December British Vogue “London Babes” story to be shot by Steven Meisel. The portfolio was being orchestrated by Isabella Blow and stylist Joe McKenna and they were searching for striking bluebloods with Meisel-level allure. The wide-eyed, gangly young writer Plum Sykes had also been enlisted on the hunt and remembers the “tiny little passport photo” that was submitted to Isabella, of Stella with her septum ring. “She was remarkable looking,” Sykes recalls, “she came in and she was just so incredibly cool that I was intimidated. She was so level headed and not vain, she wasn’t grand, she was just this really cool beautiful country turnip.” Sykes continues, “She looked like a model but was very grounded. She just looked amazing in a boiler suit—she had that incredible glamour.” “She had a nose ring—quite rusty—and it was very frightening,” Isabella Blow told me, “She reminded me of a farm animal. I can take hard tailoring but a hard look is something else—I was terrified! Her beauty was in her eyes—she was absolutely wild, like a wild bird, a tomboy who’d never worn a dress.”

Stella was also the bluest of blue-bloods. Her mother, botanical artist Lady Emma Cavendish, was the daughter of the 11th Duke of Devonshire and his wife Deborah “Debo” Devonshire, the youngest of the fabled Mitford sisters who was famously droll and beautiful and whose entrepreneurial flair transformed Chatsworth, the Devonshires’s storied family estate, into one of Britain’s great tourist destinations. Stella’s father, Tobias William Tennant, meanwhile, was the son of the 2nd Baron Glenconner, and younger brother of Colin Tennant, the 3rd Baron Glenconner, who bought the Caribbean island of Mustique with a youthful inheritance and transformed it into the playground of rock and real royalty. As an insecure teenager, Stella recalled a visit to her eccentric aesthete uncle the Honorable Stephen Tennant who had been a noted Bright Young Thing and a celebrated beauty himself in the 1920s. “The nose!” he shrieked as his great-niece walked into the bedroom where he had retreated to spend decades working on Lascar, a fanciful novel about the maritime boulevards and randy sailors of pre-war Marseilles that he would never finish, “The nose!” Stella, highly self-conscious, blushed crimson, worrying what was wrong with her nose. “Ah yes,” her great uncle continued, “… they always said I had the most beautiful nose.”

Both Stella’s parents, however, had retreated from the worlds into which they were born to raise sheep on the 1500 acre farm in Berwickshire on the Scottish Borders where Stella and her two siblings Eddie and Isabel were born. It was, Stella insisted, “A proper hill farm, not a hobby farm.”

At the time of the British Vogue shoot, Stella, a 23-year-old student at Winchester School of Art, was already on her summer holiday in the Highlands so arrived on the sleeper train from Scotland on the third day of the shoot. She had been “making an art piece with sheep’s wool from her family’s farm and diving into lanolin,” Sykes recalls, and as a result, as Issy had noted, “She was rather smelly.”

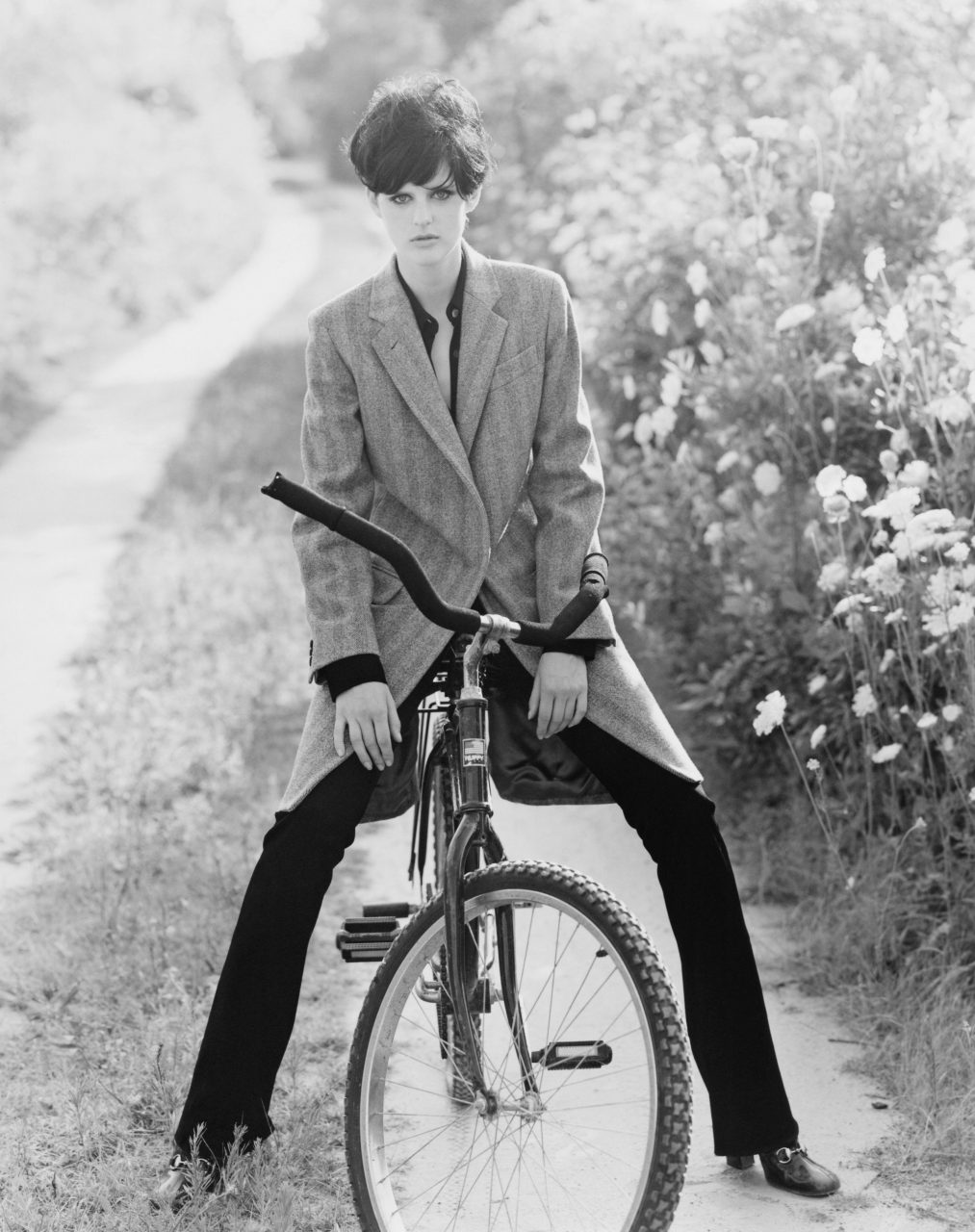

Photo by Arthur Elgort/Conde Nast via Getty Images

Vogue’s then editor in chief Alexandra Shulman wanted the nose ring removed: “There was a large disagreement about it,” Sykes recalls, but Shulman lost that battle, and Meisel’s striking images of the be-ringed Stella, eclectically dressed in such ensembles as McQueen’s tattered lace mini dress, Westwood platform shoes, and a fanciful Philip Treacy hat, dominated the “London Babes” portfolio, alongside fledgling designer Bella Freud (daughter of the artist Lucien Freud), Lady Louise Campbell (who had been flown in by helicopter from the Moet & Chandon chateau d’Epernay), convent girl Honor Fraser, and Plum Sykes herself (whom Meisel had insisted on including the moment he set eyes on her). Meisel was so smitten with Stella’s patrician beauty and achingly cool style that he asked her if she would come to Paris to shoot the Versace campaign the following week.

Initially, Stella was wary of the fashion world. “I didn’t really know if I wanted to open the door and see what was inside,” she said. “You have an idea of what fashion is about, but I’d been at art school. I didn’t know if I wanted to be objectified. I thought it was a big, shallow world and I wasn’t really sure if I liked the look of it.” Nevertheless, “I thought it was a good idea to say yes,” Stella confided, “as I wasn’t going to make a living from my sculpture, which was always about bodily functions.” Stella duly turned up in Paris, “and found Linda Evangelista, Shalom Harlow, and Kristen McMenamy in the studio,” as she recalled in a piece that she wrote to accompany her December 2018 British Vogue Meisel cover story, 25 years later. “I cannot tell you how intimidating it was! Steven photographed me just standing there while Linda and Kristen danced around me because I was too intimidated to move.” One of the images ended up on the cover of Italian Vogue: a consecration that established Stella as a star.

Despite Stella’s misgivings, the fashion world was besotted. For Donatella Versace, Stella was “strong, smart, opinionated, and determined.” She was booked for Jean-Paul Gaultier’s memorable Spring 1994 show, which represented “a startling vision of cross-cultural harmony,” as Vogue noted. A season later she walked in 75 shows. Ever pragmatic, Stella would jokingly confide that her motivation to walk the runways was that every step she took represented another acre of the fantasy Scottish or Chilean estate she wanted to buy. The nose ring eventually went too—Stella had worn it for a meeting with representatives of one of the world’s leading beauty brands and they had assumed the agency had sent the wrong girl.

But her ability to embody so many different fashion idioms—from Helmut Lang’s edgy minimalism to John Galliano’s madcap fantasy, from Versace’s high octane glamor, to Karl Lagerfeld’s haute couture hauteur—with equal insouciance, and make each her own, instantly placed her in the very small class of true fashion chameleons, up there in the Olympian pantheon with Linda, Naomi, Kate, Veruschka, and Twiggy. And by the time she entered the fashion fray, Stella was no teenage neophyte, she was a remarkably grounded and intelligent young woman, with her own agency and an objective perspective on the industry. “She wasn’t trying to be a model,” said Philip Treacy, “to be fabulous, to be cool, to have a rock-n-roll boyfriend: She was disdainful of that circuit. She didn’t care—of course, that was part of the appeal.”

The truth is, Stella didn’t have to try: She not only possessed but she defined the indefinable “it.” “She looked like a fashion sketch from the 20s,” says Sykes, “with that small pixie-ish head, amazing bone structure, and the ectomorphic body type.” Karl Lagerfeld was one of her legion admirers, responding to her beauty, intelligence, and lineage, and in 1996 booked her on an exclusive Chanel contract, ushering in a new willowy paradigm for the house, evocative of Ines de la Fressange in the 1980s, in the wake of the voluptuous blonde Claudia Schiffer. Meanwhile, Stella’s dream of a Scottish estate of her own grew ever more tangible.

Through it all, Stella remained, as I noted in 2001, “one of the most grounded people in the industry,” and her personal style was electrifying. For an October 1995’s “High-toned Tweeds” story photographed by Arthur Elgort and styled by her devotee Grace Coddington, the caption noted that “Stella Tennant favors pierced noses and navels over long white gloves and gowns … When Vogue asked Stella to model country tweeds her irreverent sense of style came with her.” As a last-minute inspiration, Elgort and Coddington had her dive into a swimming pool in her ICB tweed suit and Wellington boots. It was a one-shot moment, and Elgort captured that shot for an unforgettable image that defined Stella’s own quirky charm. In 2001, Calvin Klein presented Stella with the VN1/Vogue Model of the Year Award, which she accepted dressed in Nicolas Ghesquière’s patchwork tee-shirt, hip-slung khaki army pants, and flat Jesus sandals, looking like the most achingly cool girl on the planet. Which she was.

For the January 2004 issue of Vogue, Stella attended the Paris runway shows as a guest in the company of Sarah Mower, who noted that she had the preternatural fashion instincts of a seasoned editor. Her own wardrobe contains some of the treasures of ’90s and early 21st-century style, and she would insouciantly pair clothes borrowed from Lasnet with jewels from JAR or antique bug brooches gifted her by her grandmother. At those Paris shows, Stella admired Olivier Theyskens’s Rochas woman who she found “serene, a bit supernatural. I loved the strong structure, with softness inside, the strength and tenderness!” “I thought it was pure medical stuff at the beginning,” she said of her friend Helmut Lang, “They all had bits of bandages, prosthetics, like they’d just jumped out of their IV” and later responded to the collection’s “play of fabric, those morphic shapes, one layer peeking through another,” whilst Tom Ford’s Yves Saint Laurent was “Deco-influenced in that seventies way… And how fantastic to see those beautiful young women looking that glamorous.”

Stella had already met David Lasnet, then a photographer’s assistant, on a Mario Testino shoot. She was so smitten that when they sat opposite each other at lunch “the rice kept falling off my fork,” as she recalls, “I had to give up eating.” And when Testino teasingly told her to stop flirting with the assistant, she turned beet red and he realized that she really had been seriously flirting. Tennant and Lasnet were wed in 1999 in the small village church of Oxnam in Roxburghshire. Stella wore Helmut Lang’s first wedding dress, and when her grandmother, the Duchess of Devonshire, first saw her in it she exclaimed, “Oh darling! The bandaged bride!” It was indeed a short creation so ethereal and wispy that it was later confused for another layer of tissue paper when her mother’s own substantial wedding dress was unpacked for the exhibition House Style: Five Centuries of Fashion at Chatsworth that I curated in 2017. It had been considered lost.

Lasnet subsequently qualified as an osteopath. The couple had four exquisite children, Marcel, now 22; Cecily, 20; Jasmine, 17; and Iris, 15.

“To some degree, doing up properties has replaced my desire for making things,” noted Stella in 2003. She was then working on a wonderful West Village apartment in an 1834 brownstone with her architect friend Sebastian Alvarez who she met on her gap year in Chile. The result, as I noted in the June issue that year, was “a country house haven of sticky-fingered chintz and comfort,” and the project was such a success that when it was finished Stella cannily acquired a ruinous house nearby to renovate as an investment project. In 2003, following the birth of their third child Jasmine, the young family decamped from Manhattan to a 1748 house in Berwickshire in the Scottish lowlands, an hour and a half’s drive from the farm that her parents had moved to in the sixties. “I like the idea of being settled,” she said at the time, “because I’ve always felt that in these years of modeling I’ve been in transit.” Vogue’s Sally Singer considered the house “very much like Stella Tennant—blue-blooded but stubbornly down-to-earth.” Stella acquired it through a sealed bid system and, thrifty as she was, she was dismayed when she found out that her bid had been so much higher than the second highest. Nevertheless, she brought her wonderful taste to bear on its transformation into a showplace for her passion for antique taxidermy and exquisite wallpapers—from de Gournay to Martha Armitage. And Stella was rarely happier than when she was transforming the immediate landscape in the company of Bert the gardener.

Meanwhile, Stella consulted with Christopher Bailey for the Burberry Prorsum line. “Her influence is more about an attitude,” said Bailey at the time, “Stella has this aristocratic elegance but it’s always a bit disheveled, a bit broken down.”

Her creativity continued unabated. When she couldn’t find children’s clothes she liked enough she investigated Scottish mills and knitters and created Tennant & Son, a line of hand-knitted cashmeres, and with her sister Isabel she founded Tennant & Tennant, creating gold-leafed objects and fantastic consoles created from cast bronze branches that she sleuthed on her estate. One of them now sits proudly in the opulent family dining room at Chatsworth.

Stella returned to the fashion fray for cameos in campaigns and shows that she felt significant, and was one of the British supermodels chosen to walk the runway in the closing ceremony of the London 2012 Olympics. She wore Christopher Kane’s golden Oroton and rhinestone chainmail pantsuit, and she lightheartedly remembered that the pants were so heavy that her entire superhuman efforts were focussed on making sure that they didn’t fall down in mid swagger and create a wardrobe malfunction moment that would be seen by billions.

In 2016, Stella and her great friend Lady Isabel Cawdor, a former Vogue editor, were tapped to collaborate on Holland & Holland, the storied London-based firm celebrated for traditional hunting, shooting and fishing gear and accouterments, owned by Chanel. They researched English and Scottish mills and created collections that were wonderfully evocative of their own country lives and innate fashion intelligence.

Stella and Lasnet separated a year or so ago. She had recently acquired a handsome 18th-century townhouse in Edinburgh that was to serve as a showroom for her work, and when I spoke with her a month ago she was filled with enthusiasm for the new project.

Her loss is eviscerating to her family and friends, and the fashion industry will never know her like again.

Editor

Hamish BowlesCredit

Lead image: Arthur Elgort/Conde Nast via Getty Images