Hope can’t be passive. It has to keep on going, and if we’re to earn the right to feel optimistic, well then, we have a duty to take part in making the world better.

If the apocalyptic year of 2020 has taught the fashion world anything, it’s that continuing the way it was is not an option. Destroying the planet, perpetuating racism, hurting people who are out of sight all along the supply chain — does anyone in a C-suite, a design room, or somebody who is considering how they want to place their money as they negotiate their desire for clothes really want to be implicated in that any more?

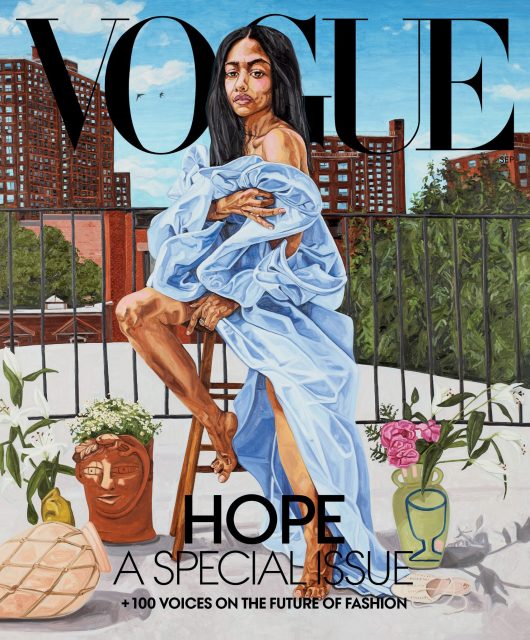

I hope not. But I struggle with the word ‘hope’. When I think of it as a rose-tinted state of escapism, I cringe. When I bring to mind that age-old cliche that ‘fashion is there to make us dream,’ it rings hollow; tinny; irresponsible to me in this age of nightmares. The only way I can make sense of it is to imagine: what kind of new dreams can fashion make realities? And whose dreams, anyway? That is the space which is now wide, wide open for fashion to reform itself.

Fashion must be more than a business

The one saving grace to me is the way that fashion connects the visual eye to the mind’s eye. What I want to imagine isn’t a glossy old-world picture, but a whole other realm of what we can consider to be beautiful: things that are probably made while taking care of people and the planet. The idea that fashion is a medium for telling the stories of the people and cultures that belong to them — and that the act of buying can invest in strengthening them. Above all, the hope that fashion can actively set about redeeming its place in society by being about more than just making money.

The Covid-19 pandemic has taught the world that we are all human, all interconnected, and that we must take care of each other. The Black Lives Matter revolution, globally, is daily demonstrating the vast difference between active anti-racism and the unexamined so-called non-racism of white constructs, hierarchies and corporations. Women activists and designers have been fashion’s longtime leaders, on the ground and the practice of sustainability. Children and young people protesting against the catastrophe of global warming have reversed the idea that elders know what they are doing. They are teaching us now.

Through the pain and shock of this year of reckoning, the fashion industry, and everyone who endeavours within it, has to chart a way forward: dismantling the bad, repurposing what exists, decolonising systems and education, uplifting and expanding the possibilities of innovation across every horizon. Listening, pitching in.

It sounds like a big old daunting thing, actively practising optimism. Hope dwindles to hopelessness so quickly when we’re all on the terrifying switchback of fear we’ve become so familiar with. Yet as I write this, members of the extended family of fashion in Beirut, who have lost their studios, collections, archives, stores and even their homes, are out in the city destroyed by the explosion on 4 August, clearing up, giving aid, acting together as a community in the direst need for change. What they demonstrate — in the midst of their far larger struggle — is something that can rally hope among individuals, even when it seems that we’re living within the grip of political systems that we feel powerless to influence.

One for all, all for one

No matter how small we feel, getting up and bonding together as individuals is a powerful way to affect change. That has been proven in 2020. When the pandemic started rolling across Europe, I noticed that the fashion graduates in Prague, their sewing skills to the fore, were the first to start posting pictures of themselves at home, making masks to distribute to their community. That was on 17 March. Since then — and still — young designers have stepped up to provide PPE when governments failed.

But then, and quickly, so did much bigger industry players. The mighty luxury fashion establishment, weighing in with its manufacturing capacity (reduced, but still functioning under lockdown conditions) essentially converted itself into an emergency service. Large brands dropped their ingrained commercial competitiveness, opened their coffers, and began saving lives, not just supplying PPE and making hand sanitisers for hospitals, but donating to fund ICU units and medical research.

That astonishing miracle happened in 2020 and I hope — using that word again — that it’s never forgotten by history, or by all those within corporations who made those decisions internally. For those who worked on the production lines — selfless heroes, we should say — their experience, and the risks they took in those scary dark days will surely be indelible stories they will tell their grandchildren in the future.

In the reset of the industry, the continuing legacy of this time can be that spirit of giving back — the gift-with-fashion purchase being not a meaningless product, but a donation to charity. That’s already happening with many small brands. The realisation that fashion is part of civil society that swept across the industry during the first months of the pandemic was a precious one. We can hope that the reform of that contentious word ‘luxury’ will now automatically include the sensation that buying — a dress, a piece of jewellery, shoes — is doing good.

The Reset

The trouble is, remembering anything from one day to the next has been a real problem in the short-attention-span mentality of the ‘Time Before’. Up until March, when the AW20 collections ended in Paris, it had reached the point where there was almost no way for people like me to recall the sheer massive volume of the physical fashion shows we attended — who was doing what for which season, who was presenting see-now-buy-now, what drop was that, who was selling direct-to-consumer, where were we travelling to next? Designers and the teams behind them were pressurised, whacked out. Everyone already knew there was a lot wrong with this — environmentally, from a mental health point of view, not to mention (which no one ever did) the elephant in the room created by overproduction. Then it stopped.

It’s been called ‘the Reset’. One of the benefits is seeing how so much that seemed written in stone really doesn’t matter any more, and how far the dissolving of rules can mean the unleashing of new talent. Since huge runway shows have become more or less impossible, or at least rare and a lot smaller, we’re suddenly witnessing a phase of wild experimentation in fashion communication.

What carries more across the internet now is not the old canon of livestreaming runways. Nimble minds freed of old preconceptions are the ones who are coming to the fore in this creative outbreak — especially young people who are authoring new worlds of filmmaking, illustration, animation, CGI. What I saw from the Class of 2020 fashion graduates — coming up with brilliantly original DIY methods of showing and talking about their lockdown collections from bedrooms, gardens and garages — far outstripped many of the digital presentations much bigger brands have made.

It means that this generation is needed by companies right now. There are new jobs, new roles, new types of commissions for different talents who can make fashion interesting, fun and meaningful in ways that were never anticipated. A large part of boundary breaking is the sensation of being able to dive much deeper than static surface appearances. A new generation is obsessed with watching documentaries and listening to podcasts. The chance to see behind the scenes, to see and hear everything that goes into fashion increasingly reveals cultures, connects with history, music, dance, literature — whole communities. It does that all-important thing of cementing the bond with a designer, who is now revealed as a person, working with people. It’s a humanising cracking of the glossy facades of the establishment that is filled with hope and potential.

Really, it all comes back to the feeling that persuading people to buy today must be from a new place of honesty, and that can no longer be pretended. A new era of transparency is something that needs to be positively welcomed with open arms by the existing fashion world.

Not that there’s any alternative in this day and age. ‘Performative’ pledges — overnight, the Black Lives Matter movement has changed the ability of millions of citizen-consumers to critique the chasms of intent hidden in corporate language. Meanwhile, creative directors who’ve been kept at an ivory tower distance from production are now increasingly expected to be able to talk cogently about sustainability policies in the same breath as the sourcing of their concepts, casting and designs du jour. If someone is talking romantically about a special jacquard or a gorgeous double-faced cashmere coat, they are likely to be asked follow-ups on where the fibres originated and who sewed the pieces. Fashion journalists (myself included) are also needing to self-reeducate.

A new generation for the industry

So, a new world is coming for new kinds of experts: people who know what they’re talking about, where their elders don’t. Students are making their way through colleges now with state-of-the -art knowledge about sustainability, bio tech, regenerative agriculture, compliance and all of the ways that creative arts and sciences interlock. Twenty, even 10 years ago, none of that existed. Every fashion company striving to overhaul itself is now crying out for sustainability officers, consultants and designers who come with ready-made knowledge about upcycling, zero waste and making beautiful things out of that which already exists.

The fact that those subjects are now being taught, however, is almost entirely due to students demanding them from fashion academics. The same now is very much true of BIPOC fashion students who have vocally risen up internationally since June to demand that courses be rewritten, fashion history decolonised and teaching hierarchies reformed.

All of this: it’s hope. Active hope, doing hope, incredibly constructive hope. It’s come up from the bottom, the margins, and the outside of every structure, not from the top down. Seeing how communities, coalitions, creators and citizens are acting so bravely, imaginatively, cleverly, joyfully in these times: this energy is the inspiration.

Can fashion wrap itself around it, merge into it, become an active part of it? That really is the biggest hope of all.

Editor

Sarah Mower