On the streets of Shanghai, content creator Shiyin can be seen wearing a traditional outfit from China’s Ming period. Popular on social media, she routinely shares fashion buys, beauty tips and lifestyle vlogs alongside all the latest from Gucci and Lancôme — but it’s her passion for Hanfu that really sets her apart.

“Chinese” clothing is often typified by the qipao (a close-fitting dress also called the cheongsam). However, Hanfu — which is defined as a type of dress from any era when the Han Chinese ruled — is seen in China as a more authentic form of historical clothing. Styles from the Tang, Song and Ming periods are the most popular; flowing robes in beautiful shades, embellished with intricate designs and embroidery.

Right now, the movement is being led by China’s fashion-conscious youth — a little like how Regency-period hair and makeup has had a boost in popularity, thanks to Netflix’s Bridgerton — and the number of Hanfu enthusiasts almost doubled from 3.56 million in 2019 to more than six million in 2020. Among those you’ll find a purist minority who abhor any historical inaccuracies, and a majority who are attracted to its fantastical elements. Meanwhile, designs can cost between 100 yuan (£11) to over 10,000 yuan (£1,100), and bought from specialist brands such as Ming Hua Tang.

What is most interesting, though, is the collective mood that’s being spurred on by Hanfu — after decades of aspiring to western trends, the younger generation is now possibly looking closer to home for a sense of traditionalism. On microblogging platform Weibo, #Hanfu has had over 4.89bn views to date, while on TikTok in China (Douyin), #Hanfu videos have been viewed more than 47.7bn times.

So, as interest in traditional cultural pursuits comes back around, is the past becoming cool once more? Here, Vogue meets Shiyin, one of the most popular figures in this rapidly growing subculture, to find out.

How did your interest in Hanfu start?

“Growing up in Canada, I watched Chinese period dramas but I had no idea that Hanfu was a thing or where to buy it. When I moved back in 2016, my roommate at the time introduced me to Hanfu and I started collecting.”

Why do you think people are attracted to it?

“I can’t speak for everyone, but I imagine most get drawn in because it’s pretty. It’s only normal, you buy clothes to look good. However, I continue to wear Hanfu because it gives me confidence in my own culture. In Canada, we had days at school where you could wear national dress, yet as a Chinese person, I had no idea what to wear. Now I know, we have Hanfu.”

How did Hanfu become one of your key content pillars?

“When I moved back to Shanghai, I worked in gaming. Gradually, I started creating my own content, and I uploaded a video about wearing Hanfu that became popular so I started producing more. I’m not an expert by any means, I’m just an enthusiast.”

How would you explain the difference between Hanfu, cosplay or role-playing games (RPG)?

“They’re all subcultures so people often think they’re the same but they’re actually very different. You can get historical RPGs, like I can cosplay a character from a wuxia [martial arts] TV show or video game but that’s not Hanfu, because it’s just a figment of imagination, it has no historical basis.”

How historically accurate are most Hanfu designs?

“A lot of Hanfu brands will reference historical artefacts, although less remain from the Tang period (7th to 10th century) but there’s a lot from the Song (10th to 13th century) and Ming periods (14th to 17th century) to refer to.”

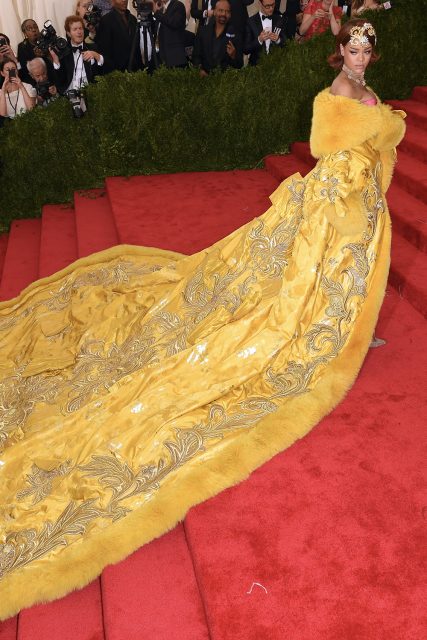

"It’s getting warmer in Shanghai now, so this is more of a mix-and-match look with a lighter robe worn for summer." - Shiyin

Photo: Peng Ke

Do you think a lot of people are inspired to wear Hanfu after watching popular period dramas?

“It’s impossible to quantify, but it definitely has an impact. When The Imperial Doctress came out in 2016, a lot of people were doing Ming-period styles and last year’s Serenade of Peaceful Joy sparked a big interest in designs from the Song period.”

On your channel, you also talk about western fashion brands. Do you see this content as being totally separate from Hanfu?

“Not really. I have a series called ‘What is luxury?’, which I started by discussing brands such as Chanel and Louis Vuitton, but now I’m discussing traditional Chinese culture. The last video was on coins, and I’m planning one on fabrics like cloud brocade (yunjin), shu brocade (shujin) and Su embroidery (suxiu). I want to show that products made in China are also ‘luxury’ — the craftsmanship of these fabrics is on a par with Parisian couture.”

In all three looks, Shiyin wears a ma mian qun, literally “horse face skirt”, a pleated skirt typical of Hanfu. With openings at the front and back, it was originally designed to make horse-riding easier, but this isn’t the reason why it’s called “ma mian” — the actual origins remain unclear.

Here, a jiaoling robe, referring to the wraparound collar design, in golden weave. “The pattern is called jiu yang qi tai, it features nine sheep and symbolises luck and prosperity. This set is made by Ming Hua Tang — they’ve been specialising in Ming period designs for almost 20 years.”

Photo: Peng Ke

Do you get a lot of attention wearing historical clothes on the streets?

“Not in Shanghai, people wear all sorts, nobody really notices… the Japanese wear kimonos for important occasions, and I think Hanfu can be worn in the same way, to show status and identity.”

How does wearing historical dress match with contemporary makeup looks?

“I often do traditional hairstyles when shooting, but usually I keep the makeup modern. Once I did Tang-period makeup with very heavy rouge and a partially drawn lip, and most of the comments online were pretty negative. It’s just so different from what we consider ‘beautiful’ now.”

Do you think the next generation will increasingly look towards China’s own cultural traditions?

“Hanfu is far from being popularised, but there is definitely a trend towards ‘China chic’. For example, everybody used to believe buying Nike and Adidas was cool, now they think maybe that can be something Chinese like Hanfu.”

Editor

Meng-Yun WangCredit

Lead image: Peng Ke